Graphic by Patty Warner/Stix Design

Graphic by Patty Warner/Stix DesignHere's a sneak peek at my upcoming column in East Village Magazine. I'm indebted to John Sonnega, a sleep researcher at the University of Michigan - Flint. As you can see, I've been working out what this insomnia thing means since my own "sleep study."

Something is keeping us awake in Flint. Did you realize? Are you one of the ones who takes a pill, even a teensy one, to get yourself to sleep?

If so, you’re not alone. Here’s something to think about the next time you’re pacing the floor at 4 a.m.: according to a 2008 survey from the Prevention Research Center of Michigan, one in nine Genesee County residents reports trouble sleeping every single night, and a stunning one-third of us rate our sleep quality as “fair” or “poor.” On average, we pop pills to get to sleep three nights a week and, for our trouble, still manage an average of only 6.45 hours per night, less than the recommended seven.

In this, amazingly, our county is not so different from the rest of the country, though the City of Flint itself is somewhat worse off than our snoozier out-county neighbors. Whether the onset of the Obama administration or the re-opening at last of the Olympic Grill, with its happy cries of “Opa!” have calmed any insomniac fears has yet to be determined. But we still have, well, the Mayor, the collapse of Generous Motors, polluted brownfields by the acre, copper thieves plundering empty houses, and plunging 401ks.

And as a very good friend of mine recently said over the last dregs of a bottle of Bushmill’s, we’re all gonna die.

When UM- Flint professor and sleep researcher John Sonnega offered the above sleep results in a talk to one of my classes recently, I took the news personally. That very day, I was groggy from a virtually sleepless night, one of many; recovering from sinusitis, I’d had trouble breathing and imagined dark scenarios. My husband said I often up wake gasping and snorting, not exactly my image of myself as a middle-aged babe. Scary apnea, he confessed, had been going on awhile.

Prof. Sonnega said there were several sleep labs in town to study us bedraggled insomniacs. My doctor sympathized, and two weeks later, my symptoms not much improved, I reported at 10 p.m. for a “sleep study” at a hard-to-find Westside lab.

It was one of the first cold nights of the year, a Tuesday, the chill offering needed relief to this year’s allergy sufferers. For the past eight hours, as directed, I’d refrained from chocolate and caffeine. I’d packed a little bag with red flannel PJs and a toothbrush.

At the end of a long maze in the dim clinic, I saw I wasn't the only one. Three others sat on the edge of low-slung beds in other rooms, getting electrodes pasted onto anxious foreheads, chests, fingertips and calves.

The tech who tended me said she can't sleep either. She works 10 p.m to 6:30 a.m., and goes home and lies on the couch. She uses the CPAP machine, just like I might have to, depending on how I do. She looks forward to winter when the snow makes the world quiet; she lives by a school and the children make a lot of noise. At night while she's watching her subjects, she reads books and studies for a sleep certificate.

She was kind and friendly, but I have to say that lab was like a cheap motel: hard pillows, bad mattress, no art on the walls, thin bedspread. How could a person, wired up like a high-tech Shiva, fall asleep like this?

At least a TV had all the channels. The box of leads slung over my top, plastic air fork up my nose, I watched Jon Stewart interview an oddly unfunny Steve Martin. Then the tech came back, turned off the lights and left me alone.

I felt claustrophobic and a bit nauseous, watching an orange light blink on a plastic thimble on my thumb. It was strange knowing somebody was watching me, monitoring my vitals. In another room, somebody coughed, and coughed again. She's worse off than me, I thought.

I muttered my mantra, a string of trusty repetitions. And then, astonishingly, I fell asleep. The next thing I knew the tech woke me up and it was 6 a.m. She peeled off all the wires and I went home.

Insomnia, of course, is not just a physiological but a spiritual problem. In the tossing and turning, the body’s anxious refusal to do what it’s supposed to do, something fearful and irrational sweeps in. Often, I turn on NPR; all night, it’s the BBC. I used to like the voices, liquid and steady as a salmon run. But lately there’s too much Congo, Zimbabwe, Darfur: too much bloodshed and pain. Couldn’t they report just one little light-hearted feature about, say, a French accordionist? Or a placid potter in Rotterdam? A recipe for butternut squash? The sad litany morphs into despair: this poor old planet, I murmur, and then I lapse into fruitless loops.

If I lived right, wouldn’t I fall asleep like my cats, who stretch out blissfully? If I only knew what’s bothering me, what I need to resolve, could I sleep then? Or maybe it’s hormones, or what I ate, or what I drank? And thus the wheel goes round.

In the meantime, the trains kachunk-kachunk along the Court Street crossings; there are sirens, the morning paper drops on the doorstep, a good neighbor scrapes snow, two joggers pad down Maxine, chatting, as they always do, at precisely 5:58. I wonder if they sleep well.

I am trying to find the peace in this. I’m trying to figure out how to tell my frayed mind that all is well, that all will be well. But the deep unconscious, like the Loch Ness monster slicing back and forth in dark water, seems to know better.

I’m still waiting for my sleep study results. But at least now I know I’m not alone – for whatever reason, a third of you are out there too, waging a similar war. Prof. Sonnega’s research suggests that neighborhood factors like fear of crime might play a role in sleep – sobering results that say we need to work together on what happens after dark. There’s a plank to lay your head on: a good night’s sleep for us all, sleep like a honeyed drink whose only hangover is waking up feeling kind of good.

Image courtesy of Jack's proud daddy

Image courtesy of Jack's proud daddy Good Read

Good Read

Graphic by Patty Warner/Stix Design

Graphic by Patty Warner/Stix Design The Harbor at 6:30 a.m. last Sunday.

The Harbor at 6:30 a.m. last Sunday. Smoke from the Yorba Linda fires, facing southeast from Pedro

Smoke from the Yorba Linda fires, facing southeast from Pedro The "Jan and Ted" Window by San Pedro artisan Mark Schoem

The "Jan and Ted" Window by San Pedro artisan Mark Schoem

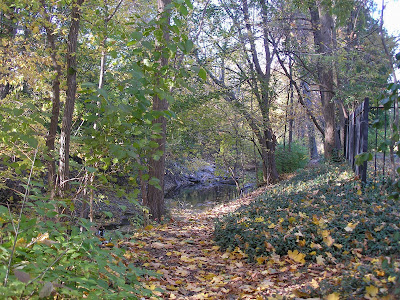

Late afternoon sun through the trees of Burroughs Park

Late afternoon sun through the trees of Burroughs Park Looking east at Burroughs Park

Looking east at Burroughs Park

Path along Gilkey Creek

Path along Gilkey Creek Entrance to Woodlawn Park Drive

Entrance to Woodlawn Park Drive Red tree on Lynwood

Red tree on Lynwood

Can you see Henriette's Egyptian eyes?

Can you see Henriette's Egyptian eyes? This is Gus, warily checking out the dining room

This is Gus, warily checking out the dining room

Reassuring Architecture, with Comfort Food in the Basement: The Flint Masonic Temple, Built in 1911

Reassuring Architecture, with Comfort Food in the Basement: The Flint Masonic Temple, Built in 1911 When in doubt, thrown in a sunset shot

When in doubt, thrown in a sunset shot

Kay Kelly Illustration by Patty Warner

Kay Kelly Illustration by Patty Warner

Saw this kitty on this roof almost every day

Saw this kitty on this roof almost every day Steps on Peck

Steps on Peck Doorway on Peck

Doorway on Peck Sunset, Pelicans, Paseo del Mar

Sunset, Pelicans, Paseo del Mar One of the tall ships leaving the harbor

One of the tall ships leaving the harbor I love the Korean Bell

I love the Korean Bell Bruegels' Tower of Babel

Bruegels' Tower of Babel